A step-by-step guide to technology startups, valuation and the VC market

We read an awful lot in the press about startups and their immense valuations. Here's a recent post from Business Insider about the 9 startups that are going to be valued at more than $10bn in 2015.

We have a lot of conversations with early stage startups who are about to take their first or second round of seed funding, and "how do I value my business" is the most common question - with examples like these quoted back to us in tones of despair.

If you're thinking about starting up or rebooting your business, these articles can be intimidating, inspiring, exciting or just plain unimaginable. But how much are these businesses like yours? And are there any common themes?

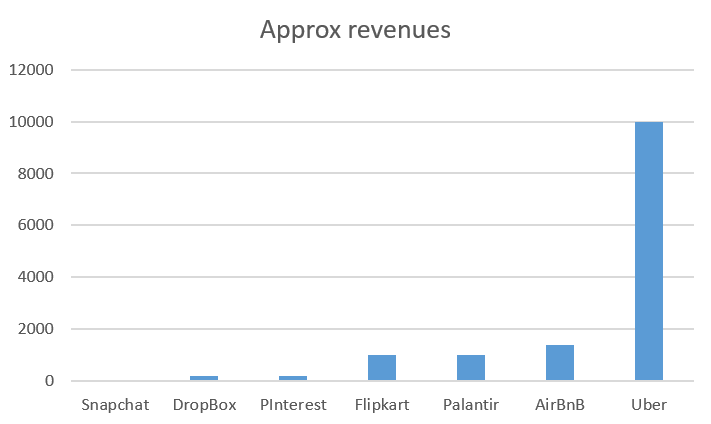

Let's look at some stats from a few of the companies from that article.

| Company | Founded | Valuation | Investment | Approx revenues | Profitable? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DropBox | 2007 | $10bn | $1.1bn | $200m | No |

| AirBnB | 2008 | $10bn | $800m | $1.4bn | Yes |

| 2008 | $11bn | $760m | <$200m | No | |

| Flipkart | 2007 | $11bn | $2.5bn | $1bn | No |

| Palantir | 2007 | $15bn | $1bn | $1bn | No |

| Snapchat | 2012 | $10bn | $650m | Nil | No |

| Uber | 2009 | $41bn | $6bn | $10bn | No |

Age

The first thing to notice is that all of these startups are over 5 years old. In fact, you could argue that they are not really startups at all at this stage; their heritage is as a startup, but they are now "something else". They have all proven that they have the ability to keep going by some means. We'll explore those means later.

Revenue generation & profitability

While they are all generating revenues, they cluster into three groups.

First, there is the "low revenue" group. In this case that means less than about $200m. Snapchat, for example, has only just started generating revenues - from selling advertising - and is probably still somewhere south of that figure.

Then, there is the "main stream revenue" group - the businesses generating $1-2bn.

Finally, there is Uber. By crikey, that's a lot of revenue.

When you dig behind these numbers, they are (excepting Snapchat) also experiencing very fast revenue growth. In fact, revenue growth is the story of these businesses.

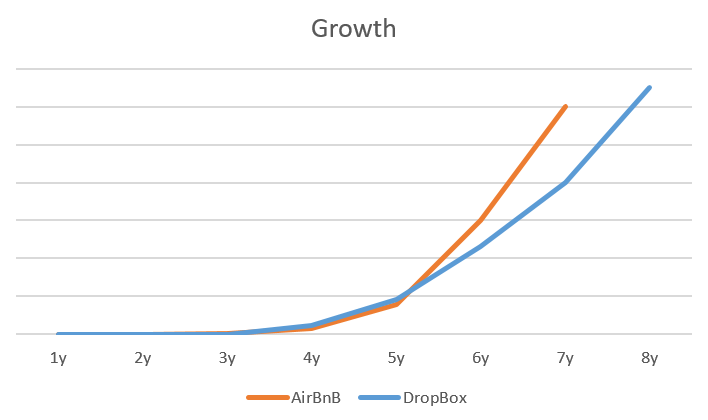

Let's take a look at AirBnB and DropBox - two very different businesses - and their revenue growth curves, based from the year of their foundation, and normalized to their current size.

Remarkably similar, no? They both trudge along the bottom for 2-3 years, then they hit a couple of years of phenomenal percentage growth in years 4, 5 and 6. The absolute growth then continues apace as they have reached a critical mass, but the percentage rate of growth is now decreasing as they find market access harder (perhaps saturation, competition or other such factors).

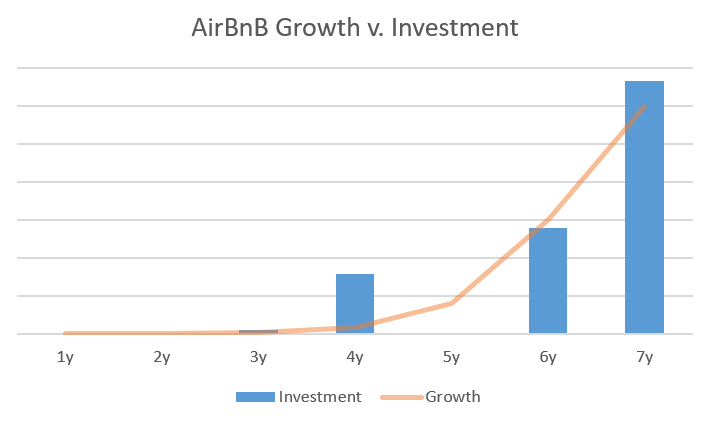

Is there a correlation, perhaps with their investment? Let's look at AirBnB again for an example.

This is a pretty typical pattern for a startup of any scale. Initial investment from the founders (often in the form of sweat equity and personal savings) is enough to keep the business going for about two years. At the end of that period, cashflow has not kept up with running costs, and, even if the business is starting to generate revenues with real customers, it is in extreme danger of going under.

What happened specifically with AirBnB is that, after some initial success in years 1 & 2, they struggled to grow deeply into their beachhead market. In year 3, based on their track record and business plan, Y-combinator made an initial $20k "keep the wolf from the door" investment, followed by a $600k "we believe in the team" investment round, which kickstarted their first phase of organic growth. 18 months later, they prove out their business model in their beachhead market, and get a significant tranche of "Series A" funding to enable them to enter follow on markets, and begin a period of growth-by-acquisition.

What is interesting about AirBnB, unlike every other business on this list is that they are actually profitable. The startup and VC world doesn't talk much about profitability. It is whispered occasionally in darkened corners when we think people aren't looking, but it doesn't really seem to matter when it comes to these astronomical valuations? Why might that be?

How businesses come to be valued

It might seem logical that a business valuation is based on its profits - after all, that's what is going to pay the bills, and the investors dividends. Well, that's true of established mainstream businesses where revenues are predictable in a well-understood market. But all bets are off for early-stage startups. It's all about hacking that revenue growth guys!

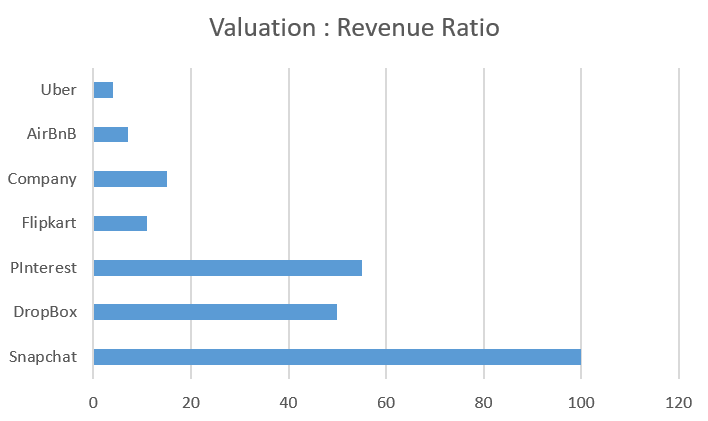

Or is it? Let's take a look at the valuations of these businesses v. their revenue numbers.

No significant correlation there. We've got a range from 100x revenues to just a few times revenues. And look at AirBnB - a high growth, high-potential business that's actually profitable, but it is at the lowly end of the valuation graph.

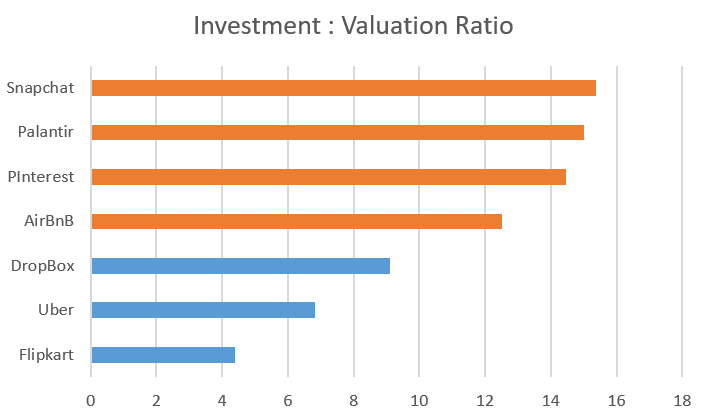

But what if we look at the investment to valuation ratios?

Now, 4 out of 7 are clustered around the 13% - 15% mark, with the remainder in the 5-10% bracket. It looks rather like the company's valuation is actually based on the level of investment in some way, not the actual performance of the company?

The market sets the price

This should be unsurprising to a good capitalist such as yourself. The market sets the price, and the valuation is based on what the market is prepared to pay for these businesses. The market in question is the VC firms.

A typical VC firm has a success to failure ratio of about 0.1, so it is no surprise that the value of their investment should be somewhere around 10% - 15% bracket. They are expecting 9 of their investments to tank for every one that comes good, and so they need to profit from that one at exit. (It's a little bit more complex than these straightforward numbers suggest - they have probably leveraged this investment through preferences, loan stock or similar mechanisms, so they probably see a little more upside on a moderate exit, at the expense of smaller investors and founders).

At this scale of investment, there are also questions of what kind of exit they are looking at.

OK, you could put $100m into the business and demand 60% of the equity (valuing the business at $166m), but that implied valuation is not a good one for the investment press, and the broader markets.

Far better to put in $100m for 10% of the business, valuing it at $1bn.

This sets market expectations for a trade sale to one of the "make a few $1bn investments a year" tech companies like Google, Microsoft, Apple and Facebook, or for an IPO in the $1bn - $5bn range.

If you sell for $4bn, then your 10% equity with a 2.5x preference becomes a whopping 10x return of $1bn on your $100m investment. Investment committee happy.

To the rest of the world, the business is already valued at $1bn pre-IPO, and it is growing (look at those revenue curves). There's got to be some upside for the canny investor there? The IPO is (at least initially) successful and everyone pops champagne corks.

What does this mean for my startup valuation

OK, you probably aren't looking for $600m of Series A funding right now. You're likely at the $20k-$1m seed funding level.

But remember when you are looking for investment that you are selling into this picture.

There are two things that are really important to potential investors:

- Your team's ability to execute

- The sunny uplands of the exit

Early-stage investors are investing in people. Not the business idea (they see lots of those, and they are mostly the same, however unique you think yours is), not the business plan, not the technology, and not even the existing customers. Those things are just evidence you can bring to bear to show that you can execute successfully within the constraints under which you are operating. They also like to see evidence that their funds will allow you to grow your revenues. Not build better technology, or allow the founders to resume their mortgage repayments. The story is revenue growth.

They are also looking for at least a 10x exit. If they put in $1m, they are hoping to see at least $10m back. Of course, they are expecting zero - 9/10 of their investments will net them approximately zero after 5 years. But if there is an exit, they want 10x.

Let's look at a hypothetical example. Our 2-year old business proves itself in a beachhead market, but is running out of cash. Whoopee! It attracts some seed funding. The VCs take $1m of investment for 30% of the equity, and a 3x pref (which values the business at around $3.5m).

What exit scenarios might we be looking at?

First, let's think about a Scenario 1: the firesale. Maybe 3 years later, trading conditions are terrible, and cashflow is killing you, but people or customers have some value? Sell the business for, say, $1m to a partner or competitor, and allow the existing investors to exit gracefully. They get their $1m back through their prefs, and the founders retire to lick their wounds and start again (or are locked into the new owners for a year or two). OK, your business was one of the 90% - but you did at least go through the whole lifecycle and have probably learned a lot.

Right - on with Scenario 2 which is the most common "success" case. By year 5, the business exits via a trade sale at $10m on revenues of say $5m.

In this example, (via their prefs) the investors make $6m on their $1m - a 6x exit. Their investment committee is not horribly angry, but they've not had a mighty success.

The founders would probably be pretty happy with that - sharing the remaining $4m would give them some financial freedom when they come to do it all again (you know you can't resist it).

Scenario 2, however, has the tendency to become Scenario 3...

What if we'd made about $10m revenues - still not huge, but... The pressure is going to be on to deliver that 10x exit - you've crossed a revenue threshold that you can leverage. What if you were to take $100m of investment now to acquire your largest competitor in a follow-on market, for example? That's a 10x revenues investment, which we've seen is well within the "plausible" range. Could you make that look like 1000+% year-on-year growth (forget the profitability?) What if that $100m was for 10% of the equity in the business, valuing the company around the $1bn mark? Could that be used as a marketing hook for the business? Sure it could.

And that's the magic trick of venture investment. It gives a moderately successful business (with a team that is proven to be above average by results) both the capital to grow, and the valuation/growth story to convince others that it will continue to deliver investor value. And that's what lets them ignore tricky details like where the profits are coming from.

Wow! This sounds like my kind of business

Well. Yes. But... Your business is unlikely to be that business. There are a handful of IPOs/sales at this level every year.

So what's the silver bullet?

These kinds of articles always have silver bullet recommendations for success at the end of them, so I will try to avoid disappointment on that front.

- You choose this path as soon as you take your first investment

- When you take your first $1m, you need to understand how that is going to take you to ~$10m in revenues, or you won't make it anywhere near scenario 3. Unless you are Snapchat.

- Remember that the investors' interests are aligned with Scenario 3 and so are yours, once you are on this path

- Remember that the failure case for Scenario 3 is Scenario 1, rarely Scenario 2

- No investor really wants Scenario 2: they will usually try to reinvest off the back of early successes before that option plays out, driving you towards scenario 3

- Really look for the opportunity to be the Scenario 3 business. If it comes, it will probably come surprisingly early in your growth curve.

But that still doesn't tell me how I should value my business?

Doesn't it? We've looked at the overall parameters, which are based on potential exit scenarios, not current performance; but the valuation for the business is whatever the investors are prepared to pay.

So, based on the current market, for $500k - $1.5m seed investment, you can expect to give somewhere around 10% - 30% of the business, perhaps alongside some kind of prefs arrangement; providing, of course, your total accessible market looks like it is going to be able to deliver scenario 3 kind of growth opportunities.

Early stage investors are getting a higher valuation for the bigger risk they are taking - they are giving you money to prove you can execute above the average, not to build a business to exit. The next round will deliver on that opportunity.

Don't waste time on complex valuation models, they don't really mean anything to anyone.

It's up to your pitching/negotiating skills to find the right investors at the right price!

The most common way to learn about this stuff is by doing. Usually, your first seed investors (or the ones who like you enough to nearly invest!) are the ones who end up teaching you this stuff, at your expense, one way or another. An even better option is to get involved with an accelerator / incubator like Microsoft Ventures, who can help you through these hurdles, without actually taking a tranche of your equity on the way.

About the author

Matthew was CTO of a venture-backed technology startup in the UK & US for 10 years, and is now a Founder of Endjin Ltd, which provides technology strategy, experience and development services to its clients who are seeking to take advantage of Microsoft Azure and the Cloud.