Endjin.Licensing - Part 5: Real world usage patterns

We've open sourced a lightweight licensing framework we've been using internally over the last couple of years. In a 5 part series I'm covering the motivation behind building it, how you can use it, how you can extend it for your own scenarios and how you could use it in a real world situation:

- Part 1: Why build another licensing system?

- Part 2: Defining the desired behaviour

- Part 3: How to create and validate a license

- Part 4: How to implement custom validation logic

- Part 5: Real world usage patterns

In this final part of the series, I'm going to take you through a real world usage scenario. The entire impetus for creating Endjin.Licensing was to provide a licensing mechanism for our new Azure based Content Management System, Vellum. From a commercial perspective, we wanted to enable monthly subscriptions, with different pricing tiers based on the different Azure Website hosting plans, instance size and number of instances, and for licensed to be locked to a specific set of host names.

From a technical perspective we wanted licensing to be separated into two halves;

- a license generation feature, that could integrate with the ecommerce process to allow customers to buy a subscription and an API which can issue a new licenses when they expire (as long as the customer has an active subscription)

- a set of validation rules that would live inside the Vellum instance to enforce the behaviour as set out by the license

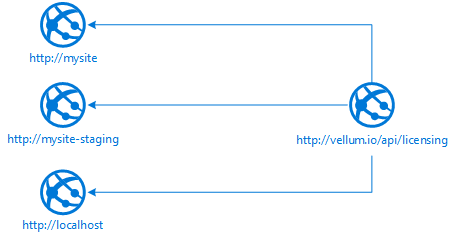

Because of the way applications are developed we need to support at least 3 different host names: localhost, for local development, mysite-staging, for sites running in the staging slot in Azure Websites and mysite for the production environment. Each instance needs to talk to the licensing api to renew their license:

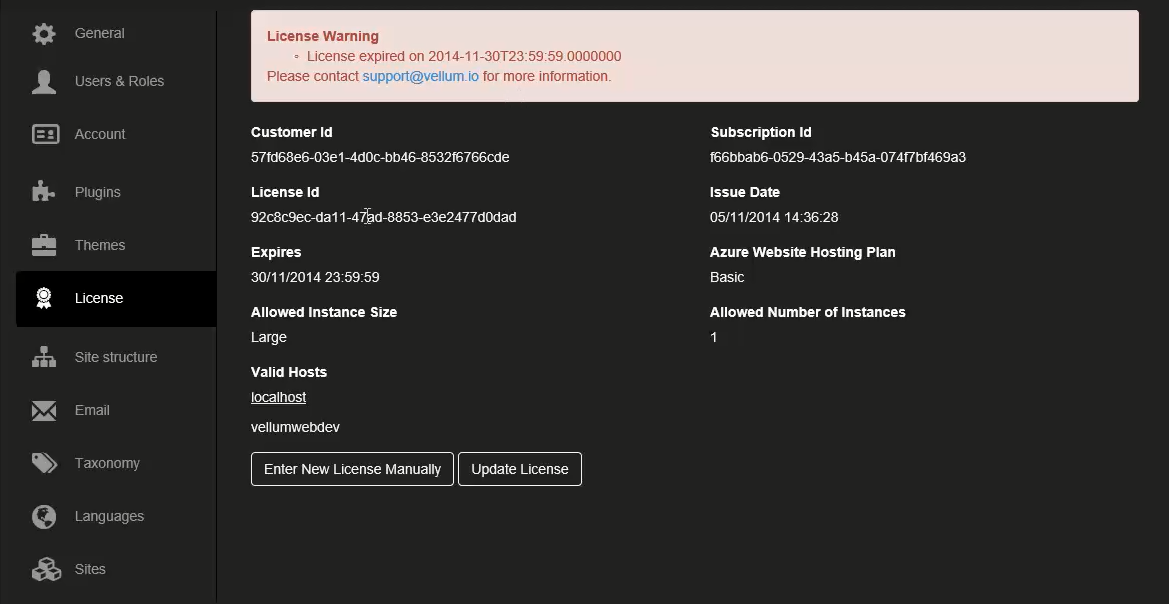

From a user's perspective, we wanted to provide a simple interface that can display all of the metadata embedded in the license, so that it's very clear how they are entitled to use Vellum. We also wanted a mechanism for them to invoke a license update and to enter a license manually, in case there were any connectivity problems:

If you compare the screenshot above to the original Specflow Scenario, you can see that the two tie up nicely.

Scenario: Free Azure Hosting Plan License that was issued today and is running on a Free Azure Hosting Plan License with a valid host name is valid

Given they want a 'Subscription' license

And their customer id is 'c8ca3109-6fbf-4b75-b6ee-67a1a0a56bd1'

And their subscription id is '03c1b02b-7806-4e94-8044-140d95ff52d1'

And their license was issued today

And their SKU is 'Free'

And their development host is 'localhost'

And their site name is 'mysite'

And they are running the site on a 'Free' Azure Hosting Plan

And they are hosting on a website called 'mysite'

And I generate their license

When they validate their license

Then it should be a valid license

And it should have been issued today

And it should expire on the last day of this month

And the metadata should have a value of 'localhost' for the development host

And the metadata should have a value of 'mysite' for the site name

And the metadata should have a value of 'Free' for the SKU

And the metadata should not have a value for instance size

And the metadata should have a value of 'c8ca3109-6fbf-4b75-b6ee-67a1a0a56bd1' for the customer id

And the metadata should have a value of '03c1b02b-7806-4e94-8044-140d95ff52d1' for the subscription id

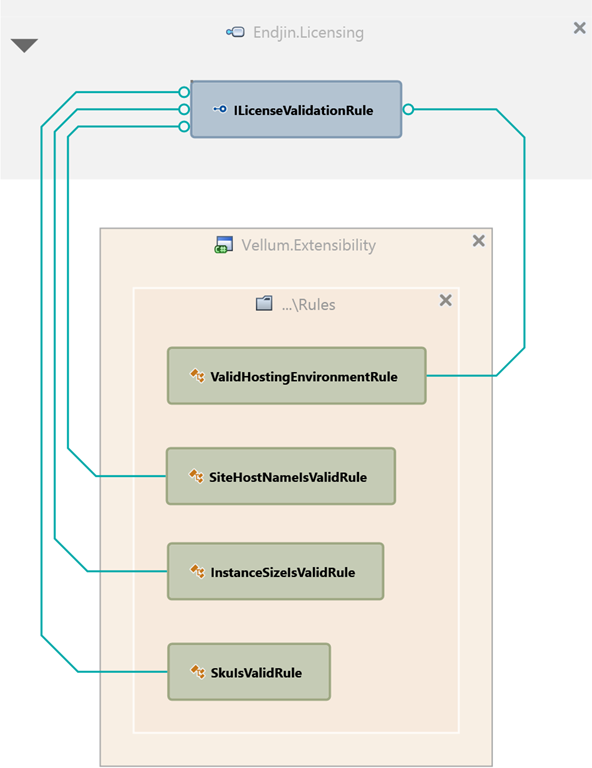

Just like the demo application in the previous post, the licensing behaviour is enabled by a series of custom rules built on top of ILicenseValidationRule:

One feature we implemented in Vellum was the notion of a "grace period" whereby the user's license has expired, but because we're nice people, we want to give them a month to sort out whatever issue is preventing them from renewing their subscription. This logic was implemented inside a Licensing Middleware class, that would alter the processing pipeline depending on the validity of the license and whether the user's grace period had been exceeded. In the demo applications, we store the Public Key in a text file that's read into the application and then used to validate the license. In Vellum we inserted the Public Key as an embedded resource inside the assemblies that needed to invoke license validation. If for some reason your Private Key was compromised, you could generate a new one, push out a new build of your application containing a new Public Key and issue an updated license.

The last point to highlight is that the whole point of Endjin.Licensing (and many other software licensing frameworks) is to act as a mechanism for users to do the right thing. Anyone with access to your binaries can reverse engineer your code (think how simple that is with tools like DotPeek or .NET Reflector) and patch them to circumvent your licensing. You can try more sophisticated techniques such as obfuscation via tools like Dotfuscator or SmartAssembly or use a packing tool like Themida which can inject unmanaged code into your assembly to prevent tools like DotPeek and .NET Reflector from decompiling them. If you're looking to use Endjin.Licensing, then I would advise you read about these techniques. There are also several interesting StackOverflow articles containing differing perspectives about the merits of code protection mechanisms – well worth your time.

Sign up to Azure Weekly to receive Azure related news and articles direct to your inbox every Monday, or follow @azureweekly on Twitter.