Step-by-step guide to bootstrapping your new product development – Part 10, Organizational Structures

Endjin spend a lot of time working with start ups and businesses who are pivoting into new product areas. They are usually operating under fierce resource constraints, and this has an impact on the way in which they can approach their development program.

We've evolved a principles-based approach to the new product development process which can be applied to a wide variety of businesses. It's based on the MIT disciplined entrepreneurship approach, incorporating great tools like the Value Proposition Canvas and the Business Model Canvas.

In this series, we're going to look at an example of a "lean" new product development process, applying these principles, and looking at some of the caveats.

There are 10 parts in the series, of which this is part 10.

1) Principles

2) Inception

3) Understanding the Beachhead Market

5) Getting to paying customers

8) Validation

9) Iteration

10) Organizational structures to support this model

Part 10: Organizational Structures

In the early days of a start up, the organizational structure is defined rather loosely, and typically by function. The technical founder has her domain, the sales & marketing founder his, and they work exceptionally closely together to achieve their initial goals.

As an organization grows, however, it is not possible to maintain that level of detailed personal control. How does a growing business structure itself for innovation? Or a larger organization pivot and allow an innovation culture to develop?

As with the rest of the series, we're looking for a principles-based approach, rather than a prescriptive "organizational structure" you should slavishly copy.

A model of organizational evolution

The archetypical start up looks something like this.

I'm the commercial founder.

I do sales, marketing,

business development, social media, customer

satisfaction, product/market fit and QA.

I also do the bins.

I'm the technical founder.

I do product design, development,

prototyping, market experiments, number crunching,

tech sales, evangelism, customer support and contract review.

I also clean the bathroom.

I'm their freelance designer buddy.

I designed the logo in my lunch hour, and

I do web stuff for them at mates' rates.

I work from home and use my own bathroom.

I'm Employee #1

I help the tech founder do the dev work.

This is my second job ever, and it is a steep learning curve.

I don't know how the bins get emptied

or the bathroom gets cleaned.

Over time, more people are needed and, by the time there are 10-15 people on board, the organization starts to look more like this.

This is still great. Everyone knows everyone else, and there is basically a single work stream on a single product - albeit that naturally people are clustering by the type of work that they are doing.

Some time round about the 30-50 people mark, however, something changes in the organization. You can no longer get everyone together in the same room as frequently as you used to (you probably don't have a single room big enough). You've got "administrative" functions that deal with things like HR and finance matters, and you have grown multiple work streams - new products are being introduced while existing products are being maintained.

The organization has started to look more like this.

Project, product and programme management functions are created to attempt to deal with alignment issues between those verticals, and the business has lost almost all of the benefits of the close-knit, cross-functional teams it once enjoyed.

How do you avoid this? Can we wind back the clock?

In any process of change, you have to start with what you've got - and, through a series of steps (either revolutionary or evolutionary) - get to something new.

We think it is easier to get an organization to change by focusing, simplifying and redefining responsibilities broadly within an established model of the business (breaking down a lot of the artificial reporting lines in the process).

It is also easier if you can do this in slices through the organization, rather than having to change everything all at once.

You can slice the cake many different ways, but we think that the fundamental principles which support any organization if it is going to be successful at innovation are the following:

Focus

It is essential that the organization is structured in such a way that it is able to focus relentlessly on its innovation projects. The previous parts in this series have been about helping a team to focus on the essentials of new product development, but those ideas will come apart at the seams if the team is not allowed to focus in that way because of other organizational demands.

Balance

The team must be well balanced. The rules and processes must be flexible, and able to adapt to the changing environment as the innovation program evolves, and the product/market opportunity and value proposition develops. The organization must not lurch in one direction then another, but be so balanced that it can respond to change smoothly, on its own terms.

Expertise

The team must have access to all the expertise it needs, when it needs it. The organization must be aware of demands for expertise, and be able to plan for making it available to the new product development team when it is needed, within the constraints of points 1 and 2, above.

Cadence

The structure of the business as a whole must have a rhythm - both at the small scale (the individual product development sprints and phases), and the large: weekly, monthly, quarterly, annually, 2 year, 5 year etc.

Governance

Decision makers throughout the business, from day-to-day operations to top-level strategy, must have access to the evidence they need to inform their decisions, without getting bogged down in too much detail. Governance structures must give sufficient freedom of operation to prevent ideas from being stifled, in return for a flow of high quality business information - without the metrics overwhelming the operation.

With this in mind, let's look at an evolution of this siloed organizational model, better focused on innovation, through the lens of focus, balance, expertise, cadence and governance.

"Scaling agile"

We want to get the best features of the start up - its focus, agility, flexibility, and cohesion - in an organization of 50 people plus. And we want to be able to make that transition smoothly from a 15-person team, all the way up to the hundreds (or even, potentially, thousands, although I personally have not helped an organization of that size scale in this way).

We are going to restructure our business units away from the traditional skills-based verticals, and organize around innovation project teams which are responsible for delivering the whole life cycle of a product (or revenue-generating unit). Each of these units is like its own "start up" within a larger organization.

Within and between the innovation teams, we identify a number of different "natural" clusters of individuals, and use them to establish the means of delivering traditional structural goals of consistency, economies of scale, best-practice sharing and synchronization of dependencies.

Here's an example of that kind of model.

. Others are more detached.

Some are strategic, some have a more reactive and tactical approach.

Some are consensus driven, some enjoy a sparring match. Some are permanently at war with themselves.

Focus

The board needs focus just as much as any other part of the business. Although the parameters will be different in different organizations, the fundamental concerns of the board should be something like the following:

- Legal and practical responsibility for the governance of the business

- The overall business strategy

- The budget for the execution of that strategy

- The creation of a supportive, constructive, safe environment for executive members to discuss the means of executing that strategy

The board should be absolutely focused at the strategic level, and delegate responsibility for execution to the executive.

Equally, it is responsible for making those strategic decisions itself; it should not ask the exec team to go away and determine the strategy for it. The exec provides the information to inform those decisions, but the buck stops with the board. If the business isn't working, ultimately, it is the fault of the board, collectively.

Balance

A lot has been written about what makes a great individual board member. But the key to a great board is balance. A board dominated by a single interest, or people of a single background (or, as is still depressingly typical, gender), will often struggle to cope with the diversity of the market, miss opportunities, and encourage the development of a mono-culture throughout the rest of the organization.

For example, if you have a number of investors (e.g. a number of angels and a small VC), the business will suffer if they end up with a large proportion of the total seats on the board. It is better to agree a single member from your investors who represents them all (usually as part of the investment agreement). That said, really great investors also make terrific advisors - but they don't necessarily have to sit on the board to do that.

It is also important to keep in mind that the board should also change as the needs of the business change. Maintaining balance means that these changes can be evolutionary, rather than revolutionary. A great board member has the judgement to know when they are no longer adding sufficient value, and can help find the right people to adapt to the new challenges and opportunities.

Expertise

The board should not be afraid to seek advice and expertise to help it with transitions, or technical aspects of the governance of the business outside of their direct experience. This may be from within the business itself, or external authorities: peers in a different domain, consultants or partners. When putting together a budget, it is important to take this into account.

Cadence

It is easy for the rhythm of the board to be dictated by its monthly or 6-weekly meeting schedule.

However, to avoid being drawn into minutiae, the smallest useful cycle is probably quarterly.

We find it useful for each meeting within the quarter to focus on a different subject - e.g. strategy, finance, operations (lightly touching upon the others in the review of previous minutes, and matters arising).

This helps keep a board meeting focused, productive, and allows sufficient time to deal with each of these issues in depth.

This steady rhythm helps you to avoid the waste inherent in traditional board activities - e.g. the run up to year end, quarterly or half-yearly budgeting.

Governance

We've talked before about evidence-based decision making - nowhere is this more important than at the board level; but it is frequently where evidence-based processes break down, and appeals to authority (in the guise of "experience") take over. There's no harm in following a gut feeling, but you should always work out how to prove it!

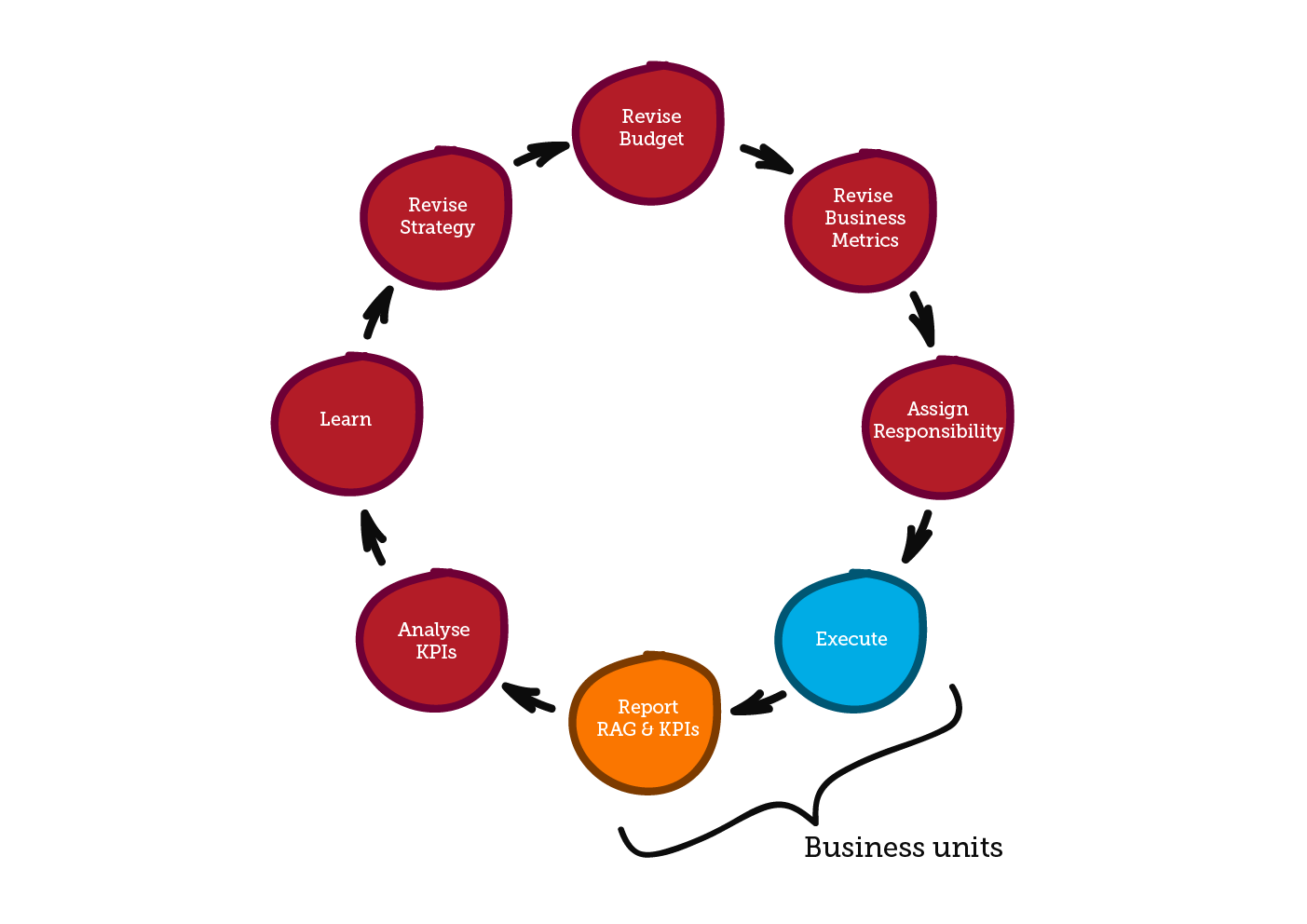

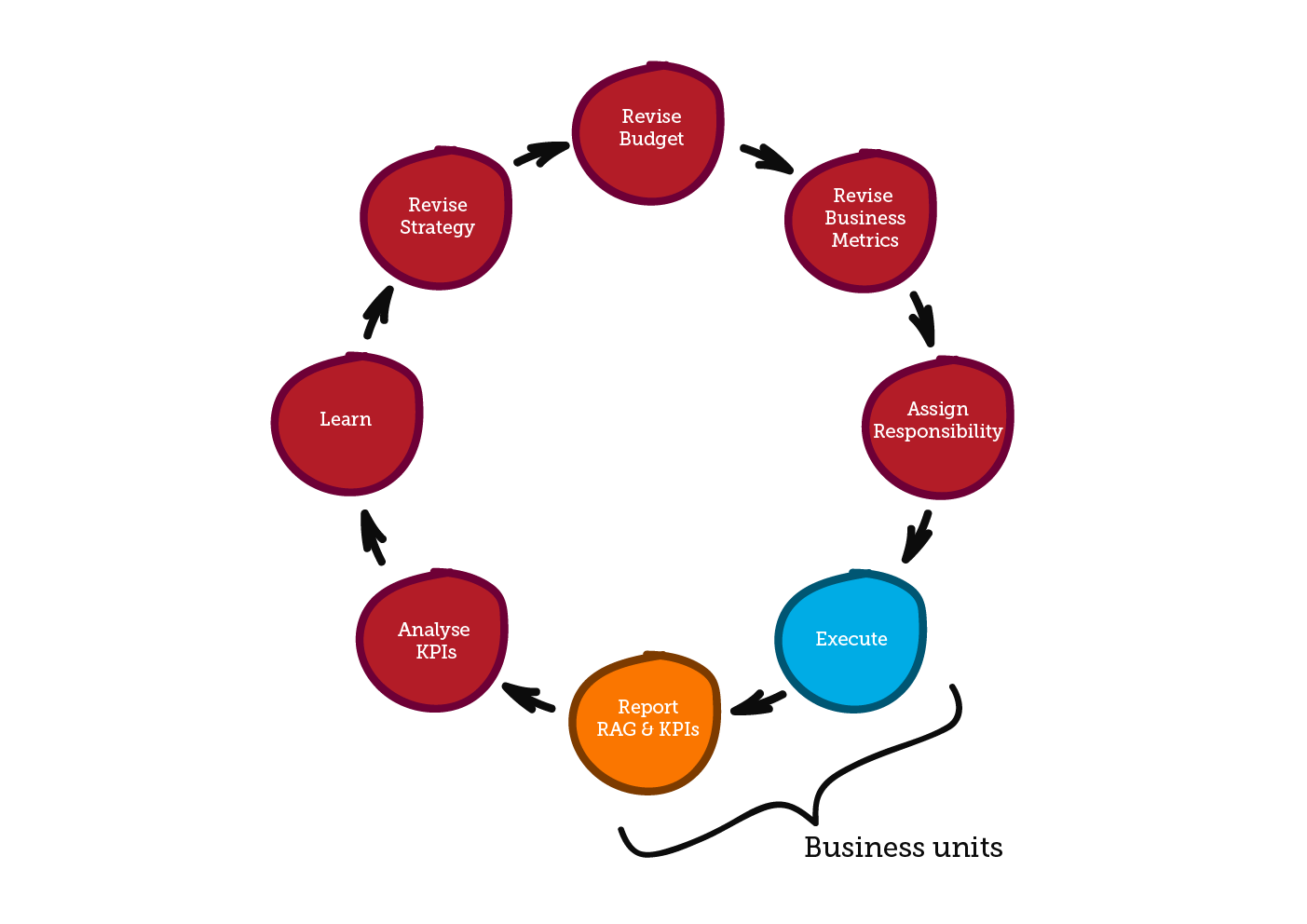

The board's governance cycle should be a variant on the same build-measure-learn cycle we use throughout the business.

The chief levers the board has in terms of governance are the metrics it defines for the business unit (or units) that execute the strategy, and the budget it hands to them to execute. The former shape both the goals and the behaviors of the business, and the budget adds a critical constraint.

It is absolutely essential that the board sets its own metrics, and doesn't leave that up to the executive.

I have sat on boards where there is no grip on the business precisely because the metrics are defined and reported by the execs responsible for various different vertical functions. The basis for those metrics changes month-to-month, and no-one understands what they are supposed to represent anyway.

Innovation Project Teams

Focus

Innovation project teams are focused absolutely on delivering on the board's strategy for a single business unit. They know what their immediate day-to-day goals are, towards week-to-week objectives, with half an eye on the longer-term roadmap (as per the previous 9 parts of this series).

Each team owns its own P&L.

The board gives them a chunk of budget to deliver measurable objectives; the board also gives them the metrics to use to measure those objectives.

The objectives are delivered using the techniques described in the rest of this series.

Balance

Clearly, these teams are multi-functional, as we have already described. Although the exact balance between, say, the more technical team members and the more commercial people will change over the course of the project, it is important to ensure that there is consistency and continuity over its lifetime.

It is also important to understand that balance does not mean a balance between "revenue generating" and "non-revenue generating" people.

There are no "non-revenue-generating" people: everyone with skills from IT infrastructure, through development, to sales, finance and HR is a part of the cost side of the equation, and their activities contribute to the revenue side.

Once you've dispelled that myth, you can focus on getting the team to gel.

Team size is very important for this (more than 15-20 people on the core team may struggle to cohere, although your mileage may vary).

It is also important to compose the team by skills, not by job title. Here's an example of a well-balanced team where there is a good mix of both overlapping and complementary primary and secondary skills, regardless of their nominal job title.

- and yet we do it to teams all the time. The very cohesion we try to encourage has the tendency to exclude those "outside" of it.

For this to work, there need to be people within the team who are specifically great at welcoming new members in, teaching the jargon that all teams evolve, and getting them up to speed really quickly. Plan time for this, too.

Cadence

This team operates at a day-to-day, sprint-to-sprint cadence. The whole team advances on the same cadence - sales, marketing and technical function alike. Even if the sales cycle for an individual customer is on the level of months, for example, the sales process still operates day-to-day, week-to-week, sprint-to-sprint.

This is a great way to avoid a disconnect between sales, marketing and development - everyone feels the same rhythm, works to the same roadmap, and understands where everyone has got to on the journey, at that day-to-day level. Teams can push slightly harder on one aspect, and dial back on another a little, to keep everything in sync.

Governance

Governance should be as low overhead as possible.

The team is trusted to break down and select its own work, because it builds that trust through a regular delivery cadence.

The whole team understands the strategy, the budget, the goals and the metrics.

The team must work very hard to be self governing (another reason why small teams like this work better together - people are less inclined to let down those close to them, than remote figures with whom they have little contact). Most importantly - no-one reports to anyone outside of the team itself.

The team culture is one of honesty, support and openness (open salary policies are an especially good idea in this environment, to help foster trust between team members, and help break down misunderstandings between e.g. sales and R&D remuneration models).

The areas of governance that most frequently require additional support are:

- Gathering metrics about the project consistently and objectively

- Identifying opportunities for process improvement

- Planning future resource requirements

- Maintaining consistency (and sharing best practices) between teams

- Managing the external dependencies of a team

We'll see how the remaining layers support this

Speciality groups

Most organizations struggle to deal with the fact that their organization requires multiple dimensions of association between individuals. They try to deal with this with complex management structures, dotted-line reports etc.

The key insight of the Spotify model is that the project team is critical, and that all other associations can be made to work without the need for a line management structure to support them.

Instead you identify "natural groupings" of interests within the business, and formally facilitate them.

Of course, every business has these groupings on an ad-hoc basis. They appear through water-cooler conversations, personal relationships, 'working groups', and they oil the wheels. What we're doing is recognizing that they are crucial to success, and enabling them as a way of doing business.

Here's a diagram that looks at the natural groupings we've identified for the model organization, at a particular moment in time.

. Taking some people outside of the day-to-day teams, and giving them responsibility for warm-and-accurate reporting, rather than project delivery, also helps avoid the poacher-turned-gamekeeper aspects of project status reporting.

Easy to adapt

Because this clustering model has no formal line-management responsibility, it is easy to apply to any existing reporting and line-management structure. As the project teams and clusters begin to take more practical responsibility, and, crucially, the board learns how to use strategy, metrics and budget to influence behaviour effectively, line management functions naturally take on more of a flavour of another "special interest group", and smaller, multi-functional delivery teams become more cohesive and self-organizing.

Conclusions

That's the end of this series on enabling innovation within an organization at any stage from start up to an established enterprise. I hope it has provided some insights, or helped you to clarify and focus your own thoughts. More than anything, we are trying to encourage critical thinking about organizations in general, and yours in particular, and establishing a more rigorous (even when light-touch) approach to strategy, decision making and organization.

Read more in the series